What is Public Narrative and how can we use it?

Table of contents

What is public narrative?

Public narrative is a leadership-development practice developed by Marshall Ganz—a former longtime United Farm Workers organizer and now Harvard professor. It’s an exercise of leadership aimed towards motivating others to join you in action on behalf of a shared purpose. It is not primarily a form of self-expression, although it does include your own vision and experiences. It includes listening and reflecting as well as telling.

Public narrative has been used successfully by many leaders and was recently used as a template by the Obama campaign’s Camp Obama.

“Telling a compelling story is how you build credibility for yourself and your ideas. It’s how you inspire an audience and lead an organization. Whether you need to win over a colleague, a team, an executive, a recruiter, or an entire conference audience, effective storytelling is key.” — Jeff Gothelf, coach, trainer, speaker, and author.

How does public narrative differ from simple storytelling?

Public narrative is a process and not a script. It’s not something to tell over and over. It incorporates the stories of others as well as your own. It’s learned and practiced by telling, listening, reflecting, and telling again. Public narrative’s aim is building grassroots power by activating people through storytelling and connecting those stories to clear policy and campaign goals.

Narrative Arts assembled people to share their stories about incarceration and organizing. (Detroit, MI)

Story of self

A story of self is a personal story that Ganz says shows “why you were called to what you have been called to.” Everyone has a story about an experience that got him or her involved in a given cause. If the cause is improving local schools, maybe one person got involved because her kids are getting a poor education and have outdated textbooks. Someone else is a local store owner who sees schoolchildren every day when they come to buy snacks. The story of self communicates the teller’s values, whether it’s “opportunity for children” or “it takes a village.” The story of self presents a specific challenge the teller faced, the choice they made about how to deal with the challenge, and the outcome they experienced. Ganz says this story invites listeners to connect with the teller.

Story of us

A story of us is a collective story that Ganz says illustrates the “shared purposes, goals, vision” of a community or organization. As with the story of self, the story of us focuses on a challenge, a choice, and an outcome. The story of us of a school-reform group might be, “Together, we are a community of local parents and residents who got into this work because we were fighting for our own kids’ educations in a failing school system—each of us wanted the best for our sons and daughters and neighbors. Then we found each other and realized the fight was bigger than just ‘my kid’—we realized that we needed each other to win this fight. And so we started this campaign.” The story of us, says Ganz, invites other people to be part of your community.

Story of now

A story of now is about “the challenge this community now faces, the choices it must make, and the hope to which ‘we’ can aspire,” as Ganz puts it. “A ‘story of now’ is urgent, it is rooted in the values you celebrated in your story of self and us, and a contradiction to those values that requires action.” There is always some discrete and urgent challenge you can present to listeners. In the case of a school-reform group, the story of now might involve getting rid of a corrupt superintendent or pressing for more public funding for education. The story of now invites people to join you in taking hopeful action on the pressing challenge, Ganz says.

Linking the stories of self, us, and now

Public narrative links these three stories together into one. Each person has her own public narrative; your story of self is unique, and your stories of us and now are similar to others in your group, though you may express them in your own way. Your public narrative may change over time. You may learn how to express your story of self more clearly as you tell it repeatedly; the shifting makeup of your community may suggest a change in the story of us; or maybe the group takes on a new, urgent challenge that requires a different story of now. Ganz writes that you don’t produce a final “script” of your Public Narrative but rather learn a process “by which you can generate that narrative over and over and over again when, where, and how you need to.”

Grassroots leaders in North Carolina practice interviewing each other as part of a Narrative Arts’ workshop. (Wilmington, NC)

How to use public narrative

Develop your public narratives

In gatherings led by Ganz and groups such as the Leading Change Network, people first learn about the theory behind public narrative. Participants spend time composing their own story of self then share it with others to get questions and feedback meant to zero in on the challenge, the choice, and the outcome in their stories. Storytellers may be asked questions such as what made their challenge a challenge or where they got the strength to make the choice they did. Other participants may give feedback, such as what images they found most vivid, what moments moved them, and how they understood the storyteller’s values. Once group members have heard one another’s stories of self, they are in a position to start creating a story of us and a story of now—using a similar process of individual writing, followed by group sharing and feedback.

Share your public narrative

A person can share their public narrative in any venue, from press releases to public events to social media. “By telling our personal stories of challenges we have faced, choices we have made, and what we learned from the outcomes, we can inspire others and share our own wisdom,” Ganz has written. “Because stories allow us to express our values not as abstract principles, but as lived experience, they have the power to move others.”

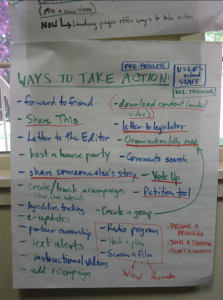

Brainstorming about where and how to share our narratives. (Richmond, VA)

Examples of public narratives and its outcomes

- Camp Obama in Burbank, California has videos of campaign volunteers’ stories of self, us, and now.

- James Croft gave a five-minute speech on bullying and LGBTQ suicide that has a “self, us, now” framework.

Explore more

- Marshall Ganz’s Public Narrative worksheet, which is the source of most of the quotes in this chapter.

- Public Narrative participant guide, adapted from the work of Marshall Ganz.

- Marshall Ganz Q&A on the Narrative Arts blog.

- Global Health Leadership Program, Public Narrative coach training manual, adapted from the work of Marshall Ganz.

- Tom Hanks wrote an op-ed supporting a bill to fund community colleges that tells stories of self, us, and now.