Case Study: Globalgiving/Rockefeller Foundation

OVERVIEW

- Project summary: Method of gathering “micro-narratives” from large numbers of people in areas where partner organizations work in order to yield qualitative data for program assessment and growth. Also serves the field of international development.

- Narrative challenge: Keeping the stories coming in organically, with only volunteer field staff managing the scribes.

- Evaluation metrics: Number of organizations that use the story data in grant proposals and for decision making.

- Websites: GlobalGiving.org RockefellerFoundation.org

“Rebecca’s life has come to an end with doctor’s announcement that she was pregnant. Her father immediately disowned her and her mother ran short of options…” That could be the first couple lines of a gripping novel. Instead, it is the start of a paragraph-long story by a 30-something woman in Kibera, Kenya. It’s one of over 40,000 “micronarratives” collected in Kenya and Uganda by GlobalGiving, a website that allows users to donate to vetted development projects around the world. (Since 2002, more than 300,000 donors have given over $85 million to some 8,000 projects.) In 2010, the organization launched its Storytelling Project with the intention of learning about the experiences of the people in areas where beneficiary groups are located. The project was supported by a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation.

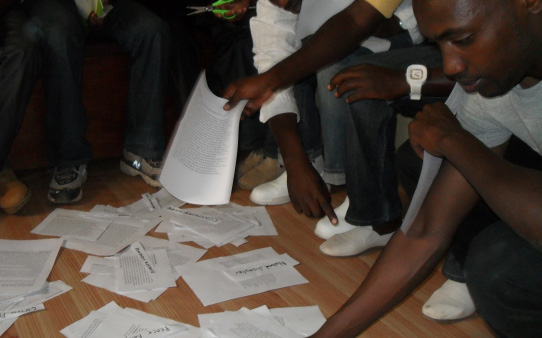

“Most of the organizations that raise money through our site are low-budget grassroots groups,” says project coordinator Marc Maxson. “So it only makes sense for the story-gathering process to be equally grassroots.” GlobalGiving’s local partners hire and train “scribes,” who then have community members fill out a GlobalGiving storytelling form, which asks, “Tell us about a time when a person or an organization tried to change something in your community.” Storytellers also give their age, gender, and location and tell what the story is about, how it makes them feel, and so on. All that information gets fed through a host of tools the organization built to produce data about community needs, possible solutions, and innovative organizations that it might add to its online platform.

“This project addresses

the challenge of how to

evaluate a portfolio with

many small discrete

projects that were not

planned together. It

combines the human

aspect of individual

stories with an analytical

way of analyzing trends

and patterns across

the body of stories to

see the bigger picture.

What’s next is setting

standards for evaluating

the quality of stories—for

accuracy, completeness,

representativeness.”

—Nancy MacPherson,

Rockefeller Foundation

The benefits of this method are many, says Maxson. It gets groups invested in the process of evaluation. It helps overcome the “self-report bias” that hobbles so many international development projects—in other words, it collects stories from more than just the people who are already motivated to share their experience. What’s more, by analyzing word frequency and other aspects of enormous numbers of stories, it neatly combines anecdotal and statistical data. And, not least of all, it’s fun for the storytellers, in a way that filling out a questionnaire is not. Visitors to the organization’s website can use interactive tools like maps and word clouds to view and analyze stories themselves. Maxson says, “Our goal is to shorten the survey and make the mapping questions more flexible so each organization can use a personalized version of it.”

There’s another big advantage to this system: It’s relatively cheap. “There are thousands of small organizations that will never be able to afford or manage typical monitoring and evaluation functions,” Nancy MacPherson, managing director of evaluation for the Rockefeller Foundation, told the Stanford Social Innovation Review in 2011. “This could be a way to help smaller grantees be more systematic.” Rockefeller’s investment in the project may benefit the entire field of development, and other fields as well, as the project expands. The ongoing challenge, says MacPherson, is “how you use a body of stories to provide rigorous qualitative evidence.” GlobalGiving is still wrestling with how to deal with a bias toward “optimism,” which compels people to tell stories with a happy ending. The organization’s findings will be a set of principles on the use of narrative.

And Rebecca, from the story at the beginning? Vocational school turned her life around, and she became a hairdresser. Once rejected by her family, Rebecca now pays for her three siblings to attend school, supports her sick father, and opened a shop for her mother. She even has a car, and her “bouncing baby boy goes to a good school.” That’s not just a nice story about an individual striver; together with thousands of other micro-narratives, it may enable GlobalGiving and the groups on its website to change, well, history.

View some of

View some of

GlobalGiving’s

micro-narratives

on an interactive

map.